CAN THE TUGENDHAT VILLA BE LIVED IN?

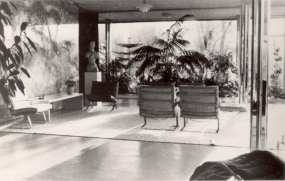

This provocative question was voiced by the art historian Justus Bier. This was a reaction to an article on the new structure of the Brno Villa in the magazine 'Die Form' which was published in the year 1931 by the publisher himself Walter Riezler. The commissioners themselves entered into the polemic on the theme as to whether “the Tugendhat Villa can be lived in” with their reactions supplemented with a text by the architect Ludwig Hilberseimer. The Tugendhats rejected the view that the monumental, impassioned living space would only allow for a kind of ceremonial or showpiece housing, and in contrast expressed their complete satisfaction with its variable character. The unforced domestic calm also radiates from the family photographs by Fritz Tugendhat who was a photo enthusiast and amateur filmmaker.

From the philosophical perspective the Tugendhat Villa particularly reflects the influence of the German Catholic Modern movement. The American art historian Barry Bergdoll as well as the Czech art historian Rostislav Švácha have pointed out in this connection the ideas of the philosopher Romano Guardini, one of the most significant figures of German Christian Personalism. Mies had met with Guardini and his ideas had additionally influenced Grete Tugendhat. “Large spaces provide freedom. Space has a completely special calm in its rhythm which cannot be provided by a closed room.” The snaps by Fritz Tugendhat are genuine personal interpretation of space in contrast with the 'official' photographs of the architecture. “When I allow these spaces and everything which is inside them to influence me as whole, I clearly feel: what beauty is, what is truth.” The Tugendhats apparently knew Guardini’s views or at least discussed them with Mies. Guardini’s works, which came about at the same time as the design of the Villa, state that a well-built internal space has levels which lead into depths. This is precisely the manner in which one enters downward into the space of Tugendhat Villa the intimate character of which is protected by the stern street section of the house.

Art historical theories and interpretations of not only Tugendhat Villa but Mies’ work in general will continue to stimulate generations of art historians and architecture theoreticians. Up until now almost all of them have agreed that the essence of the Brno realization was the arrangement of the main living space and its connection up with the external outdoors. One of the starting points was undoubtedly the ideas of F. L. Wright and his “open plan” which at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries removed the four walls demarcating the rooms allowing for the emergence of a continual space with a connection to the exterior of the structure. Mies van der Rohe himself did not write anything about the Brno Villa, but he did discuss the conception in detail with his educated clients.

This country’s leading, and by coincidence also from Brno, art historians view “the loose” and “the open” space of the house as analogical to the architecture of the Middle Ages and the Baroque. Václav Richter compared Mies’ space conception with Santini’s radical Baroque space in the pilgrimage church on Zelená hora near Žďár nad Sázavou. Richter’s student Zdeněk Kudělka has made reference to the Neo-Gothic aspects of this space which is enhanced by a cross-like connected profile of steel supporting columns and the mirror-like gloss of its chrome cladding. These interpretations coincide with Richter’s remarkable periodization of the history of “the open” architectural space which was in his view only fulfilled in the Gothic, in the radical Baroque and in the skeleton architecture of the 20th century.

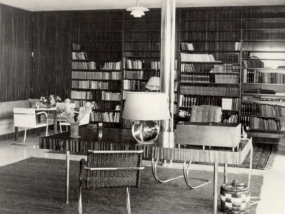

Mies’ student Philip Johnson and after him the Swiss architecture historian Sigfried Giedion have interpreted the interior of the Brno Villa as “a flowing” space whose “flow” is only gently channelled by the lines of the onyx and the Macassar inner wall in harmony with the regular rhythm of the supporting columns and the carefully placed furniture.

The period Czechoslovak specialised journals ostentatiously ignored Mies' realization in Brno. The only positive evaluation of the building in the domestic press came from the exclusive society magazine Měsíc (Month) which presented the Villa as one of the crowning expressions of contemporary aesthetic and technical maturity. The negative attitude by Czech specialised circles would thus seem to foreshadow the painful future of both the Villa and its inhabitants.